Last year, I had the privilege of reviewing Interrogating Pregnancy Loss, a groundbreaking collection of scholarly and creative nonfiction essays that explores pregnancy and infant loss in all its complexity and heartbreak. While this book features a number of deeply affecting chapters, there is one in particular that captured me from the very first read—not only because it is a poignant and beautiful piece of writing, but also because the author’s disarmingly honest account of losing her firstborn child so closely reflects my own experience.

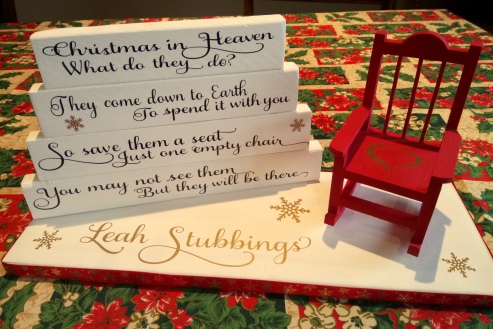

I can still vividly recall my first time perusing the book’s review manuscript on a sunny Saturday afternoon, all the while feeling a tiny baby boy kick against my pregnant belly. Initially, I had been reluctant to serve as a reviewer, knowing how triggering the subject matter would be as I continued to grieve for Leah, while also navigating my ongoing fears of losing another baby. But at the same time, immersing myself in other women’s stories of loss continued to be a cathartic form of therapy, not only because it helped me feel like less of an alien in a culture that prefers to ignore experiences of stillbirth and infant death, but also because, oftentimes, my peers are able to articulate aspects of my grief and trauma that I haven’t been able to put into words.

This is one such story. When I read Rachel’s chapter for the first time, I had to stop halfway through. Every candid thought and emotion she expressed was so eerily similar to what I had experienced with Leah, it felt like I was reading my autobiography. When I finally finished the chapter, I broke into sobs. And then I read it again. And again. And again—each time crying heartily and thinking: “If I could pick one piece of writing that would help people better understand what my experience with infant loss has been like, this would be it.”

As such, it is truly an honour to share the following guest post by Rachel O’Donnell, reprinted with permission from Demeter Press.

__________

Rachel O’Donnell is a writer and teacher who lives in Rochester, New York, with her husband and two living children, and the memory of her daughter, Corrina. She can be reached at racheltodonnell@gmail.com.

Full Term Baby Loss: A How-To Guide For Mothers

Beginnings

When you find out you are pregnant, call your best friend. Say: “I thought I was, but the first blood test came back negative!” Think: they really spring it on you, this whole pregnancy thing. Say to her, with a mild groan: “I am already eight weeks along.” She laughs, because she has had her baby for two years now.

“Don’t worry,” she says, “This is why babies take nine months to cook. You have plenty of time to get used to the idea.”

So you try. Walk up and down the street, a belly proudly displayed in front of you, a womanly being with thick hair and clear skin who responds to questions with motherly charm. The questions are easy: “When are you due?” and “Is this your first?” and “Do you know if it’s a boy or a girl?” Answer each with a toothy smile. Become a lover of small clothing, doula cooperatives, and wooden baby toys. Walk confidently like a grown-up and a mother, someone who is responsible for someone else.

Order decaffeinated coffee, swear off soft cheese and heat all your food until the boiling point. Throw up in the mornings and sometimes in the afternoons. Make kale salads and take your daily tablets of DHA with acceptable herbal teas. Refuse to use the microwave. Pick out a house with multiple bedrooms and on moving day, do not lift any heavy boxes. Research front baby carriers, back baby carriers, jogging strollers and nursing bras. Interview pediatricians. Go to the baby store and register for important things: a set of cloth diapers and wipes, an organic changing pad cover. Ask questions and take notes: what is that thing that fits snuggly over the car seat and why do you need it? Do you go to La Leche meetings before or after the baby comes? You are given a car seat and a bassinet. These are the things you will need.

When a classmate pours you a beer to celebrate your successful qualifying exams, turn it down. Order sparkling water instead. Think: everyone noticed you did not drink it, and with your obvious weight gain and disappearing waist, everyone knows. Later, on the subway, say to them all: “I am pregnant.”

They turn to you and smile. “Good for you!” they say, but what they really mean is: how in the world will you have a baby and finish your dissertation? Start sweating. You yourself do not know the answer.

On Saturdays, go to yard sales and pick out gender-neutral clothes: a yellow footie pajama set printed with ducks, a white fuzzy zipper suit for the cold.

At the midwife’s office, drink a sugary substance and flip through parenting magazines as you wait for two hours to pass. Lie down and listen to the heartbeat through the fetoscope. Watch the spinning centrifuge determine your iron levels.

Take afternoon naps and learn to sleep on your side. Buy more pillows. Go to prenatal yoga classes and lean back gently on the bolster, interlacing your fingers and placing them on your belly with your eyes closed and the lights dimmed. When the instructor tells you to imagine the life growing inside of you, feel the life hiccup and kick your hand.

Endings

Your first maternity clothes are a borrowed pair of jeans with an elastic band, and you are wearing them again, at the end, when your water breaks in the mall and soaks you to your feet. That day, the midwife comes and listens again to the heartbeat. You rest again on your side, wait for contractions to get stronger, and wash the soaked jeans.

Soon, the midwife returns and cannot find the heartbeat. Where did it go? It was just there. Watch her listen again. And again. She takes the fetoscope out of her ears one side at a time. Watch her mouth moving. Something about going to the hospital, should be able to find it, going to double check. Say: “I want the baby.” The midwife looks at you with a sad face. “I know,” she says.

Get in the car and fasten your seat belt. Look over at your husband and say: “There is a dead baby inside me.” You don’t know how you manage to say this to your husband so matter-of-factly and later, you will remember this as a moment in which you did not yet understand. You somehow thought the baby would still appear.

You are cold in the car in your pajamas. Park on the roof of the hospital and walk from the snowy parking lot through a heavy door. This is all you will remember later. How long was the trip to the hospital? Did you talk to your husband and the midwife on the way? What would you have said?

Walk down some stairs and into a brightly lit corridor and through some special door with a buzzer. Everyone in blue oversized jackets stares as you lie down on the table. Watch as they put gel on your giant belly and start the ultrasound, the wand moving over and over and over.

Stare up at the lights and then turn your head to the left, where there is a large window. It is still snowing. A new doctor comes in and presses harder with the probe. You stare to the left without blinking until he says your name. He asked the midwife what it is and that is how he knows. Again he says your name. Again he says it. You cannot look at him because you know what he will say and then finally you turn your head and see his head covered in a paper cap and his blue scrubs and his kind face says it: “I cannot find a heartbeat.” He says your name again because you have looked away from his face and back up to the lights.

Say quietly and disgraced: “Why did the baby die?”

Hear the pity in his voice before he speaks. “I don’t know.”

After that, after the news has been revealed and you are assumed to understand it, there is a lot of quick movement and noise. Hear words like IVs and morphine drips. People move in and out of the room and there is discussion of the changing of shifts.

You wait and wait and wait for it to end. There is only that one kind doctor and every time someone appears that you have not seen before, ask what time the nice one will be back. Think: why did he leave without letting you know?

At night, you sleep on your side and your husband sleeps in the folding chair next to you and holds your hand. When you get up to use the bathroom, do not look in the mirror.

When the midwife comes back into the room and reports that she has called your parents like you asked her to, realize that this is the first time you cry. You have always been a disappointment to them. Here you go again, producing a dead baby instead of a living one.

Someone puts a long needle in your back and tells you it will help ease the pain, but it does not.

Finally, you tell them you have decided on the c-section because the baby has been dead for days and you cannot get her out. See that you have failed many times at this whole motherhood thing: you can neither produce a living child nor deliver her properly.

They wheel you down the hall. You ask them to give you a strong sedative for the surgery and they do, but still you can see the blank faces of the doctors, the bright lights and tubes tied to your arms, and feel the pulling when they get her out. They seem to hand her to a nurse, who quickly leaves with a large blanket. You don’t know where they have taken her.

When you are in a new room and the surgery is over, you are so happy the belly has gone that you breathe a sigh of relief. Think: “It is over!” For many years, regret this thought. You have wished for an ‘over,’ but there is no ‘over.’ Rather, there is a before and after. There is so much of a before and after that some days you can no longer stand the sight of your smiling wedding photographs, before you knew what was to be soon after. Or not be.

Your parents come to the hospital and talk briefly and seriously. They remember a friend whose baby died during her pregnancy forty years ago, who had to wait months to deliver. “Before Pitocin,” they say.

“Oh,” you say, “that is sad.”

They place a salmon-colored mug with an attached spoon and some white carnations on the windowsill of your room. Later, when they are gone, open the small envelope attached to it and read what they wrote: “Get well soon.”

Funny, you think. You did not know you were sick.

The midwife comes in and tells you they took pictures. You are surprised at this news: surely there was nothing to take pictures of. You cannot even imagine it. When she tells you that the baby had a beautiful face, whimper softly because when they told you she was dead, you had thought she was a monster. Try to picture the baby with a body and a face, but you cannot.

A nurse who seems flighty and overworked but not necessarily unkind reveals to you that the dead child you produced was a girl, even though you have asked not to be told the sex. A daughter. This is all you have ever wanted. You were waiting all this time for that girl, that beautifully gendered baby girl.

For two days, you do not want to see her. Finally, on the third day, you say it is okay when they ask and you wait. A different nurse opens the door and comes in with a small bundle wrapped in a white crocheted blanket. Later, they will give you this blanket to take home, when it is empty. She places the bundle in your arms and it has a tiny knit hat so all you can see is the face. The nurse tells you not to take her hat off because of the autopsy, it is resewn. Think: “Frankenstein’s monster.” Look carefully at her face. Think about touching the dark hair sticking out from under the hat, but you do not do it because you are afraid. Her face is perfect, with a tiny nose between some light bruises and above bright red lips. When you touch her forehead with your finger, you are surprised it is cold. She is tiny but heavy so you give her away quickly. See, in the corner of your eye, your husband crying and kissing her face again and again. You can only kiss it once before you hand her back because it is very, very cold.

Years later, your biggest regret is this: giving her back so quickly. Now, though, it seems like enough and you are frightened and just want to go home. List the things no one tells you about pregnancy: the swollen ankles, the difficulty breathing when you walk upstairs quickly, the questions from strangers, and that you only get to take your baby home if you have produced a living one.

Also, later, when she is gone, you wish you had thought to look at her feet.

Refrain

At home, at first, it is better. You can take the sleeping pills they prescribed for you and sleep in your own bed, even though you cannot lie on your side from the pain and you must wear a sports bra at all times. Once, when you take it off to shower, look carefully at your nipple and see the white liquid you produced for her leaking out.

When you wake in the morning, feel fine, refreshed, the sleeping pills must help! Then: remember it. Remember it all.

Look in the mirror at what you have: a bereaved body living in two times at once. Your pregnant body was two bodies, but now you are less than one.

Later, when you are out of sleeping pills and still in bed, you cannot sleep. And you are very, very alone: there is no person in your belly and no baby on the outside. Where did she go? Oh, right: you lost her. Look quickly behind you like a woman who is losing her mind.

At night, when you try to fall asleep again, hear a baby crying. Try to shut this off. Instead, get up and look around for the baby, even in the basement. Check the washing machine. Say: “Just in case.” Remember: when you were in the hospital trying to force your uterus to contract and deliver your dead baby, you heard living babies crying too.

You have a dream that you are giving birth in the hospital, pushing hard, and they place a tiny white kitten on your chest. They tell you the kitten will die. When you wake up, think: “Oh, thank god! It was only a kitten!”

Send your husband back to the hospital for the baby’s things. There is a tiny handmade box with her pictures and the white blanket inside it. In the photographs, she is long, stretched out. This bothers you. In them she is lifeless, with red lips, darkness around her eyes, and a bruised body. You can see how she should have been moving. Seven pounds, three ounces. Say: “Perfect.” Touch the picture of her face and put it away.

The next day, look through what you have left: a couple of photographs, some black footprints, a small teddy bear the nurse placed between her hands in the pictures, a pink hat, and a cast of your big belly you took on one of the last days.

The baby room door is closed. Behind the door, there is a lamp in the shape of a rabbit. There is a hand-me-down crib, a dresser, a sketch of a bunny and a dragonfly you bought and framed.

When the midwife comes later, beg her for specifics because you cannot remember. Do you remember the doctor putting a probe into you to find out if you were contracting during those days you spent trying to get her out? “No,” you say, you do not remember. You do remember the midwife rubbing your feet. You remember asking her if you would have to push. You remember that when she told you your milk would come in, you covered your chest with one arm and sobbed. When you were pregnant with a living baby, this was the only way you could imagine her: nursing at your breast, a tiny hand in your hand, a sweet smelling head on your chest.

Ask the midwife about that smell. The lock of hair they taped to her footprints smells like a baby. Say: “What is that? I always thought it was baby powder.”

“No,” she says and shakes her head, “babies smell sweet.” This makes the tears run down your face without stopping, thinking about the sweet smell of babies. Your baby.

Get up and check the mailbox. For ten days in a row, you get one sympathy card or more in the mail before they end and you don’t need to check the mail anymore. Your mother’s sister writes in her card that her cat Gizzy died. Crumble the card and throw it into the trash.

When spring comes, try to go for a walk. See the overabundance of mothers with living babies walking them in strollers. Then, getting on the school bus, there are little girls. They have pretty dresses and barrettes in their hair. Soon you cannot even go to the corner pharmacy. Try the supermarket instead. There, when you are in a long line behind a mother and a small baby, abandon a cart full of groceries and walk quickly to your car in the parking lot.

Tell yourself you will one day again cook dinner or play the piano, but today is not that day. You cannot read or listen to music: these are the things you and she used to do together.

Go to the baby store to buy a baby book during your one moment of hope that someday there will be a living baby in your house. On the shelf, you see a machine to listen to your baby’s heartbeat. Pick it up and read the outside of the box, the long paragraph that describes how it can be used to prevent stillbirth. It ends with an exclamation point! Place your chin to your chest. Why, why did you not get that machine?

On a good day, you feel like it will be okay, that someday you will be a mother. On a bad day it is not even close.

Imagine yourself dead. Imagine yourself pregnant. Decide you want both, or perhaps neither. Think hard about how you will answer the question, “How many children do you have?”

Keep a list of things people should and should not say to a mom like you. Under ‘OK,’ write: “We miss her too,” and “I’m so sorry.” Under ‘Not OK,’ write: “I can’t believe you missed my birthday, “ and “You are not the same person.” These are the most painful ones, written in the letters you get later on from the people who were supposed to be your friends. One of the worst ones ends with, “This is not the you I know.” Remember: you no longer know yourself.

Shut up, you say to the letter. Shut up, shut up. Soon phone calls from these people make you throw up violently and without warning, like you did when you were first pregnant. Unplug the phone.

Think about death. Wish for your own. Wish to go back to the moment of hers. You were there, after all, watching her slip quietly away.

List things that are difficult: peeing next to the baby changer attached to the wall in the department store bathroom. Ordering coffee next to the woman in line fussing over a baby picture. Walking by the baby clothes in the superstore. Tiny shoes of any color. “Mommy!” called by a small child.

Try not to wince when people show off their pregnant bellies.

Years later, still notice the gap: the family portraits, the number of grandchildren, the order of the cousins, the preschool class, the bus for school children that passes your house, the father-daughter party that no one has invited your husband to attend. This will continue for years to come, but you do not yet know this, and it is somehow better.

Keep your list of ‘OK’ and ‘Not OK’ in case you need to add to it later, which of course you do.

Sustained

There is a support group for people like you. When you go, you hear the term ‘babyloss mama’ for the first time. Think: you do not want to be here. You do not want to be one of them. Baby loss mama. The word mama is there but with some horrible identifier in front of it.

“I always feel like some kind of dead baby mama freak bag,” says one. Say: “Oh, you too?”

Another one says, “When I held her in the hospital, I cried and cried all over her because I wanted my tears to go with her when they took her away.”

“Oh,” you say, “that was a good idea.” Curse yourself for not thinking of that.

The one with the unwashed hair says, “When people ask me why she died, I don’t know what to say because I probably killed her.”

“How do you think you killed her?” you ask. She gulps and coughs and wipes the tears off her cheek. She says, “I drank a cup of coffee and that was probably it.” You try not to laugh. This is ridiculous. This is trying to get the maternal body to behave responsibly. Coffee is at fault for none of this.

After the meeting, think: you yourself almost certainly killed your baby by not paying enough attention. Or maybe it was that soft cheese. Another miscalculating mother at fault.

You start seeing a therapist. She starts many sentences with “other parents who have lost children tell me,” but often you cannot make out the rest because you sob loudly. You are glad for this phrasing, though, especially the “other parents” part. You don’t know them, but you imagine them in their big suburban houses with their other children running in the yard. Funny, they are dead baby freak bags too.

Your husband, who is both an atheist and a physicist, takes you to where they have put her ashes. It is behind a big gate and full of plants and trees. He insists that her molecules are with us. He can calculate this. “See,” he says, scratching some numbers on a wrinkled yellow page from a legal pad, “there she is.” He grins proudly and circles the dots on the page.

Later, when you are alone, throw some dirt in the air. Watch it fall down, get into your hair, and leave dust on your face. Whisper: “I miss you.” Say it out loud: “I miss you, baby girl.”