I am honoured to share the following guest post by fellow loss mama Shanecia Cadena. Any comments or questions for the author can be sent to Cadenashanecia@gmail.com.

You never truly know how precious life is until a horrible tragedy unfolds before your eyes.

June 30, 2016 began as a normal day. I was 22 weeks along in my pregnancy with my daughter, Gabriella. In the morning I felt my baby girl moving around and kicking as per usual. That afternoon I had a routine prenatal checkup, which I hoped would confirm that she was still growing healthy and strong. However, little did I know that this appointment would change my life forever.

My obstetrician started off by asking the usual questions. She discussed Gabriella’s measurements, and then we reached the part that I always anticipated yet also silently feared: Searching for her heartbeat. At my previous appointments finding her heartbeat with the Doppler had been quick and easy. But not this time. It took longer than expected and I immediately knew something was wrong when I saw the worried expression on the doctor’s face.

Soon she rolled in the ultrasound monitor to see if it could detect what the Doppler had been unable to find. When this didn’t work, she left to ask the head obstetrician for help. Shaking and scared, I began crying and praying that this was just a glitch, and perhaps my daughter was simply being stubborn. The new doctor came in shortly afterward and performed another ultrasound. After what seemed like a lifetime, he began explaining what he found on the screen. He said that Gabriella had a lot of fluid and swelling around her head. He then confirmed that she had passed.

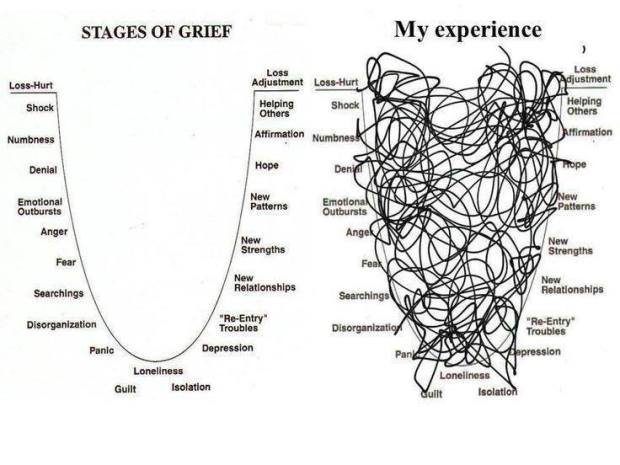

In that moment my worst fears had come true. I was so heartbroken. I was in shock. I was numb. It was the worst feeling I could possibly imagine.

Crying uncontrollably, I called my husband to tell him the devastating news. The doctor had indicated that I could wait and let my body go into labour on its own, or I could be induced later that day. I couldn’t hold off any longer; I was admitted to labour and delivery soon after. As they wheeled me upstairs to my room, we passed by walls adorned with beautiful newborn baby pictures. It broke my heart to know that Gabriella’s photo would never be displayed and celebrated in this way. So many thoughts were running through my head: Why was this happening to us? What did we do to deserve this? What did I do wrong?

Hours passed before I was given medicine to start the long induction process. I kept asking myself, “Can I do this? Am I strong enough to handle this?” I could feel my stomach deflating like a beach ball. Time continued to creep by and at 7pm I finally started pushing. It was the worst physical pain I have ever experienced, although it did not compare to the heartbreak of losing my baby. She was born still on July 1 at 7:13pm. We were given a day to hold her and spend time with her before she was sent to the funeral home.

The doctor would later inform us that Gabriella was diagnosed with Turner Syndrome, which only occurs in female babies. She had fetal hydrops and cystic hygroma, all of which translated to a 1% chance of survival. However, it took about six weeks for us to receive the results of the biopsy that had been performed on her skin and umbilical cord, at which point we were told that the tests were inconclusive. It wasn’t protocol for the doctor’s office to make sure the cells were fresh, and the lab did not run the tests within 48 hours like it was supposed to. It kills me that we will never know her cause of death for certain. Even though the doctors are confident in their diagnosis, I will always wonder.

It has been just over a month since we lost our baby girl. We go about our daily activities and routines, but each day remains a struggle for me. Not a day goes by where I don’t think about her or picture her precious face here with our family. While we are not completely healed, it is comforting to know she’s at peace and watching over me, her daddy, and her big brother. As much as I want to forget about what happened, I can’t. Our family will always love, cherish, and miss our sweet Gabriella.